Collingwood council heard from its inquiry legal team both in public and private sessions on Tuesday for the first time since the conclusion of the Collingwood Judicial Inquiry.

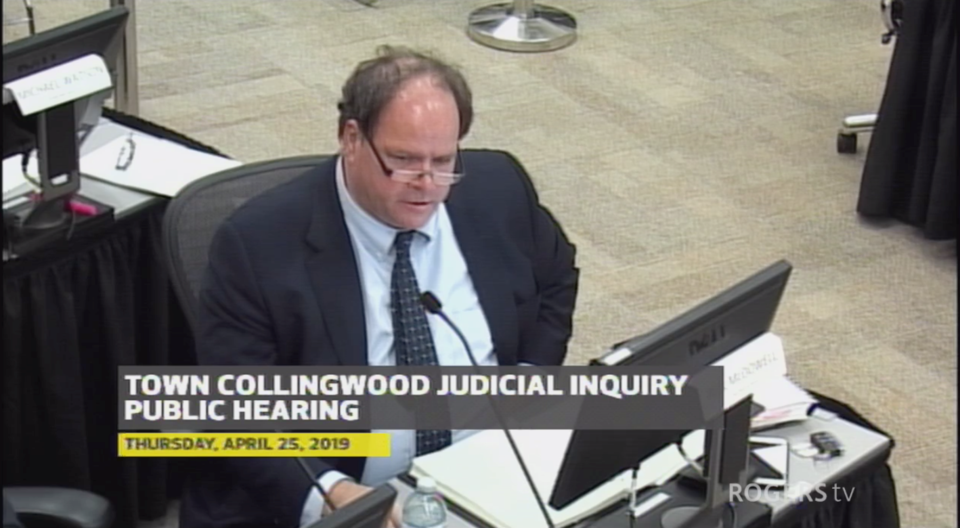

Will McDowell (of Lenzcner Slaght) and Ryan Breedon, both of whom were hired to represent the town during the inquiry, appeared before council on Feb. 16 to offer a debriefing following the commissioner’s report delivered in November 2020.

McDowell took the lead on the public portion of the presentation, indicating he was glad the town had some answers after years of rumour and innuendo.

He was hired by the town prior to the inquiry to conduct his own investigation into the 2012 share sale, but told council his investigation only raised more questions. It was on his recommendation in Feb. 2018 that council requested a judicial inquiry into the matter.

“There was no effective substitute,” said McDowell during the Feb. 16 meeting. “The town had the ability under the municipal act to appoint an auditor to look at a subsection of transactions, but it’s not the same thing as saying to a witness, ‘I have your documents and now I want you to come testify before a judicial officer.’”

He said the ability of a judicial inquiry commissioner to subpoena records and testimony is what made it the only option for the town.

“The town could have said, ‘we’re going to live with it,’ or it could have done what it did,” said McDowell. “My only regret about this inquiry is the cost.”

Initially, staff reports suggested the Collingwood Judicial Inquiry would cost between $1 and $2 million. To date, the town has spent over $8 million.

“As somebody who recommended looking into this, at some point you think, ‘what if I’m wrong?’” said McDowell. “But it became pretty obvious pretty quickly … there was something to see here.”

He noted there were millions of documents to be sifted through, and ultimately nearly half a million documents included as evidence after being vetted by the commissioner’s legal counsel.

Breedon said it was his responsibility to handle town documents for the inquiry.

“A majority of the documents were produced by the town,” he said, adding many of the documents were emails and email chains from town accounts.

He said the town didn’t hire a document management company to do an internal review of the documents and eliminate duplicates, instead they gathered what was “likely relevant,” and turned them over “en masse” to the inquiry for review.

“Other parties would have done an internal review to filter out what was not relevant,” said Breedon.

McDowell said document management is costly, but it’s necessary in the 21st century.

He confirmed the town could not have changed or stopped the inquiry once it started, even as costs escalated.

“For reasons of judicial independence, that’s not a realistic option,” said McDowell. “Your predecessors on council knew this on the front end.”

Instead, council sets terms of reference and provides that scope to the commissioner, who then investigates the matters included to “his or her satisfaction.”

“I believe that it was [properly scoped] because the terms of reference were crafted in such a way to say the commissioner could have a free hand in examining these two fundamental transactions,” said McDowell.

The town asked the commissioner to investigate both the 50 per cent share sale of Collus to PowerStream in 2012 and the subsequent decisions that led the town to spend the proceeds of the sale on two recreation buildings made of fabric membrane structures.

Councillors asked their legal team if they thought the report laid any blame or found fault in those involved in the share sale and recreation facility deals.

“The commissioner opened the proceedings by cautioning everybody he didn’t have the ability to make civil or criminal findings,” said Breedon. “But he certainly did go on to make specific findings with respect to conduct.”

Breedon said it was noteworthy that Commissioner Frank Marrocco referred to the public outcry over the two transactions in his introduction and said the outcry was justified.

“In terms of achieving what he was asked to do, I think he did,” said Breedon.

McDowell said Marrocco’s report does criticize the “players,” in particular PowerStream, former Collus CEO and Collingwood CAO Ed Houghton, and former mayor Sandra Cooper and her brother Paul Bonwick.

“During the course of this inquiry … it frustrated me that some of the people were in the position to have said ‘here are the facts and here’s everything you need to know,’ but they didn’t do that,” said McDowell. “In some instances, they came to the inquiry and over and over and over maintained there was nothing to see here and nothing wrong had been done.”

However, he argued the 900-page report from the commissioner and his more than 300 recommendations for changes to municipal policy, procurement procedures, and provincial law shows the opposite.

“Yes, these were matters that did warrant investigation,” said McDowell.

Council also had a closed session with the legal team from the inquiry, which was to include recommendations from Breedon and McDowell on further legal actions the town could take in light of the findings in the commissioner’s report.