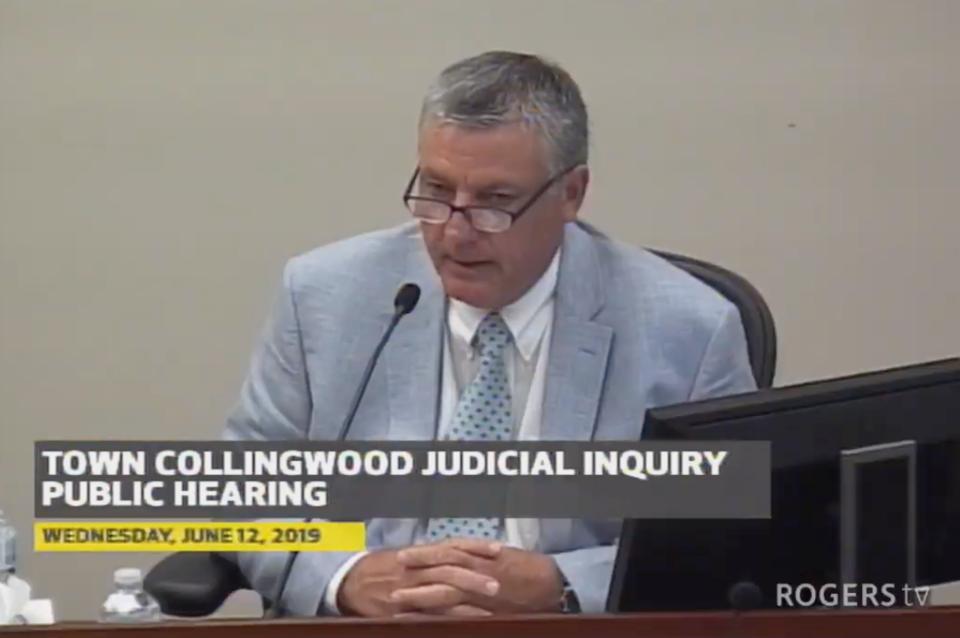

Paul Bonwick said he “should” have done more to build confidence from the public in the deal that led to the town purchasing and building two recreation facilities.

Bonwick is the brother of former mayor, Sandra Cooper. While she was mayor, his company, Greenleaf Distribution, was paid approximately $750,000 in consulting fees by BLT Construction, the company hired to build and install the Sprung fabric membrane structures for Central Park Arena and Centennial Aquatic Centre.

Throughout the judicial inquiry and in his closing submission Bonwick maintained he informed Ed Houghton and Rick Lloyd of his contract with BLT Construction. Houghton was the acting chief administrative officer (CAO) for the town at the time, and Lloyd was the deputy mayor.

Bonwick also said he went through the process of disclosing his consulting work with PowerStream in the 2012 share sale deal, but learned the municipal conflict of interest act did not include siblings in the list of family members who could present a conflict of interest for municipal council members.

During his testimony, he noted he did not see any other laws or policy indicating he needed to disclose his work to the rest of council or town staff.

“In hindsight, I now believe that it is inadequate to simply follow the letter of the rules and regulations,” he said in his closing submission. “I should have made additional efforts beyond those considerations in a sincere attempt to ensure confidence in a process in the eyes of the community.”

Bonwick’s company, Greenleaf, received a consulting fee that represented 6.5 per cent of the contract between the town and BLT Construction. Greenleaf was paid by BLT after the contractor received the first cheque from the town.

During the inquiry, there were several questions raised about this consulting fee.

Lawyers for the inquiry and for the town asked whether Greenleaf’s fee increased the cost of the facilities to the town, effectively making the town pay Bonwick’s fee.

Bonwick and BLT both maintained the fees came from BLTs profits, and were not paid by the town, nor did they impact the bottom line.

“I made one condition very clear,” wrote Bonwick regarding his dealings with BLT. “That any fees paid to Greenleaf must come from BLT and in no way would Collingwood absorb additional costs as a result of our business agreement.”

The size of the fee relative to the work was also questioned during the inquiry.

Bonwick defended the fee in his submission, saying his work went beyond the Collingwood contract.

He argues he helped BLT create a “turn-key” model intended to be promoted across the province “and beyond.”

“To be clear, this approach that I was recommending had the potential to secure many tens of millions of dollars in new business across Ontario and beyond for the Sprung/BLT partnership,” said Bonwick.

In a closing submission by the town’s lawyers, they argue the contract between Greenleaf and BLT “bore little resemblance” to what Bonwick actually did for BLT, and suggested the clause stating Greenleaf would supply leads for future business to BLT was “fictional” because BLT/Sprung already had a strong lead with Collingwood through Lloyd and Houghton before Bonwick was involved.

The town claims Bonwick’s role was to “influence behind closed doors” to ensure the deal went through.

"In sum, Bonwick did not cause the Sprung/BLT proposal to be sole-sourced, but was instead a kind of insurance policy for BLT towards that end," states the town's closing submission.

Bonwick argues the deal was done through a public council vote with a majority (8-1 for the arena and 7-2 for the pool) voting in favour of purchasing the facilities.

He stated councillors “quite often” seek advice from friends, family, colleagues and members of clubs and church groups, and can access “a multitude of information sources” to make a decision.

“Any final decision is the sole responsibility of the individual elected,” said Bonwick.

Bonwick claims he did not try to conceal his participation in the deal, but the town argues he did.

“I should have handled it in a much more robust manner similar to my involvement in the Collus share transaction,” he said.

In his closing submission, Bonwick said he learned from the expert presentations during the final phase of the inquiry perceived conflict of interest is “every bit as real to the electorate and should be given equal consideration.”

He suggests the town could require extended disclosures even beyond family members for “greater transparency for those involved in the decision-making process.”

Bonwick said he supports the idea of a lobbyist being held to similar rules of conduct that govern elected officials, and suggested a mandatory training program for potential lobbyists in Collingwood, at the expense of the lobbyist.

“Canadians have witnessed an unprecedented level of access to information and resulting scrutiny on information that led to decisions made by elected officials,” wrote Bonwick in his closing submission. “I would submit that it is moving the structure or types of interactions between lobbyists/agents, elected officials, and staff from a very informal, casual, and non-transparent environment to a more structured, accountable and transparent environment.”

The inquiry continues though public hearings have concluded.

Commissioner Frank Marrocco will prepare a final report on the inquiry with his own recommendations and any findings of misconduct he deems appropriate. He did announce the report could be out as early as February, but it would likely take longer.