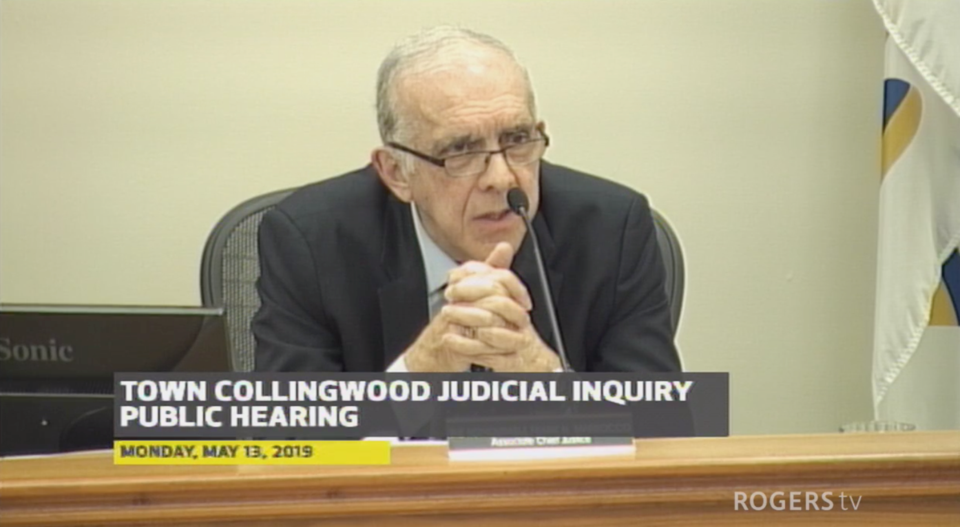

In 2019, the hearings for the Collingwood Judicial Inquiry brought more than three dozen witnesses to the stand.

The inquiry was called by a vote of council in February 2018, and public hearings began in April 2019.

Council asked the inquiry to look into the 50 per cent share sale of Collus to PowerStream in 2012 and the subsequent spending of the proceeds from the sale to cover some of the costs of two fabric membrane structures built as recreation facilities.

According to Associate Chief Justice Frank Marrocco, commissioner for the Collingwood Judicial Inquiry, there have been 61 days of hearings, 650 pages of foundation documents prepared by the inquiry, half a million documents submitted by participants, 14 experts, five panels, and 14 affidavits.

The inquiry hearings were split into three phases. The first phase dealt with the share sale and included 29 witnesses testifying at hearing dates from April 15 to June 28.

Part two looked into the spending of the proceeds and construction of the Central Park Arena and Centennial Aquatic Centre. Hearings ran from Sept. 11 to Oct. 24 and included 14 witnesses.

The third part of the inquiry was called a “policy phase” and hearings ran from Nov. 27 to Dec. 2 with panels of experts on good governance, municipal law, procurement, and lobbying. Their presentations were intended to help inform Commissioner Morrocco as he prepares his final report for the conclusion of the inquiry.

This month (January 2020), participants in the second phase of the inquiry may submit closing statements.

Marrocco initially said his report would be ready in February, but it will likely not be available until later in 2020.

Inquiry costs hit $5.2 million in 2019, and staff have estimated another $700,000 in inquiry bills for 2020.

The 2012 Collus sale resulted in proceeds of about $8 million for the town.

“This is a significant investment by the Town of Collingwood, both in terms of the finances that we have dedicated to this investigation, as well as the staff resources,” said Collingwood Chief Administrative Officer Fareed Amin. “I would probably say that this is perhaps the largest investment per capita by any public entity in Ontario, or indeed across Canada.”

Collingwood staff report the town has used up some of its contingency and emergency reserve funds to pay for the inquiry costs, and will have to draw from taxation in 2020.

CollusPowerStream was sold to EPCOR in 2018 for a total of approximately $14.5 million.

The outcome of a public inquiry can include findings of misconduct by the commissioner, but the commissioner does not lay criminal charges or make findings of criminal liability.

Marrocco, on several occasions, has stated an inquiry is not a trial.

Honourable Denise Bellamy, the inquiry for the Computer Leasing inquiries in Toronto, reiterated that point in a chapter on how to run a public inquiry in the book Public Inquiries in Canada: Law and Practice.

In her chapter, she reiterated the differences between a criminal or civil trial and public inquiry - as Marrocco has done - while she was commissioner over the inquiries in Toronto.

“I did so because I could see that people wanted blood,” she said. “They wanted someone to be held accountable, to be penalized and to go to jail if need be … Punishment or penalty may well follow, but not as part of the public inquiry itself. To this day, people still complain to me that no one went to jail.”

The outcomes of the Toronto Leasing Inquiries (there were two simultaneously) were policy changes at the city of Toronto, and according to expert testimony at the Collingwood inquiry, those policy changes have also been implemented in other Ontario cities like Ottawa and Vaughan.

Bellamy made 241 recommendations in her final report. They included practical applications such as establishing a lobbying registry, codes of conduct for council and staff, training on those codes of conduct, and hiring a full-time integrity commissioner.

Since her report, the province has passed a law requiring all Ontario municipalities to have an integrity commissioner on contract. Collingwood uses the integrity commissioner services obtained by the County of Simcoe.

The Walkerton Inquiry was called in 2000 after seven people died and more than 2,300 Walkerton residents became ill from contaminated drinking water. The report released in 2002 included 121 recommendations from the commissioner and the inquiry for the province of Ontario. Every single one has been implemented, according to Public Inquiries in Canada.

Recommendations from the Walkerton inquiry led to the Sustainable Water and Sewage Systems Act and the Clean Water Act, which governs drinking water treatment for municipalities across Ontario.

The province also spent $50 million to build a training and education centre in Walkerton for owners and operators of municipal drinking water systems.

The Ipperwash Inquiry was called when a man, Dudley George, died after being shot in a 1995 protest by First Nations representatives at Ipperwash Provincial Park.

One of the outcomes of the inquiry was the return of Ipperwash Park to First Nations people.

A judicial inquiry into tainted blood being used for transfusions in Canada resulted in a complete overhaul of rules for testing blood by Canadian Blood Services.

Ontario Court of Appeal Chief Justice Dennis O’Connor was the commissioner for the Maher Arar Inquiry and the Walkerton Inquiry.

“We should not write off in Canada the institution of the public inquiry on the basis that recommendations that are made in public inquiries inevitably gather dust,” said O’Connor in the Public Inquiries in Canada book. “That’s not the history in Canada.”

Outside of policy, governance, and procedure changes, the book’s authors argue inquiries can produce other important results.

Pierre-Olive Brodeur was a member of the policy research team at the Charbonneau Commission in Quebec, which was called to investigate potential corruption in the management of public construction contracts. Aside from implementing recommendations to change the way public contracts were awarded and managed, Brodeur said it uncovered information and made it public which meant nobody could deny corruption was a problem in Quebec.

“The mentality of the public has changed to the point where no politician will even accept tickets to a Montreal Canadiens game,” said Brodeur in the Public Inquiries book.

While there has been no information released about what recommendations might be contained in Commissioner Marrocco’s report, the policy advisory phase focused on the areas of procurement, lobbying, and good governance.

“I think the recommendations coming out of this inquiry will have a significant impact on municipalities across Ontario,” said Amin while he presented during the policy phase.

Amin called the inquiry comprehensive and noted he felt it was a necessary exercise.

“I supported it because I think it was important that the people who live, work, and do business in Collingwood understand what occurred in the initial sale of the hydro shares, and secondly, how the money derived from that sale was spent,” he said.

Currently, inquiry staff will be working on compiling information and informing Marrocco for his final report.

“It’s no small undertaking that we were asked to undertake,” said Marrocco on the final day of hearings.