Danielle Turpin will never forget her last shift at the nursing home. It was a heartbreaking day, forever seared in her memory. But as awful as it was, the tears she shed on the job inspired her to try something drastically different—something she strongly believes will help improve the quality of elder care right across the country.

A personal support worker in Peterborough, Ont., Turpin was employed for two years at a municipally operated, not-for-profit care home. She was initially optimistic that, due to government oversight, the quality of care would be a lot better than what she witnessed at some for-profit facilities during her 15-year career as a PSW. She was sadly mistaken.

Like so many seniors’ homes, Turpin’s workplace scrambled to deal with constant staff shortages, and the employees who did show up were often exhausted and forced to cut corners. There were never enough resources to go around, which ultimately meant less face time with clients. And that was before COVID-19 came along and made a bad situation infinitely worse, exposing the chronic problems plaguing Ontario’s long-term care facilities.

It was June 2020—three months into the first wave of the pandemic—when Turpin finally hit her breaking point. “This lady really had to go to the bathroom, but she needed help to get there,” she recalls. “So I’m running around trying to find a Hoyer lift. Even if I find one, I still have to wait for somebody else to help operate it.”

As Turpin rushed from room to room, the ring of bedside call buttons filled the hallways. “By the time I got back to this lady, she’d had an accident and was crying,” she says. “Then I started to cry. That day, I finished my shift and never went back.”

Turpin was determined to find a better way forward: to somehow figure out how to provide quality care to seniors without overwhelming the frontline workers responsible for administering that care. “I wanted to go out on my own,” she says. “I figured I could decide how I would take care of myself as a worker, and how I would take care of my clients.”

After months of research, Turpin settled on a bold plan. Along with a fellow personal support worker, Amy Firlotte, she co-founded Home Care Workers’ Co-operative Inc.—the first-ever PSW-owned worker co-op in Canada. Turpin hopes it will be the first of many. She is convinced, along with other experts, that the co-op model holds great promise for sparing seniors from the devastation that unfolded in long-term care homes over the past two years.

“PSWs are the experts when it comes to providing care,” Turpin says. “So we need to hear those voices about how we can change the system from the inside.”

The current system certainly didn’t protect seniors from the pandemic. According to the latest statistics, one-third of all COVID-related deaths in Ontario (4,446 of 13,361) were elderly people living in long-term care facilities. Many died alone, cut off from the world and isolated from loved ones. Not surprisingly, seniors and their advocates are now taking a hard, honest look at how they want to spend the twilight of their lives—and all options are on the table, from community housing to multi-generational living to improved homecare.

The co-operative concept should be part of the conversation, Turpin says. Although hers is the first worker co-op of its kind in the country—owned and operated by the very people who provide the frontline services—it stands as a potential blueprint for others to follow.

“Overall, co-ops tend to be more durable in times of crisis, and that’s partly because they are less risk-seeking than investor-owned firms and they develop in a way that has an eye on the long-term future,” says Jen Budney, a researcher at the Canadian Centre for the Study of Co-operatives at the University of Saskatchewan. “They typically form during times when the market and/or the government is failing communities.”

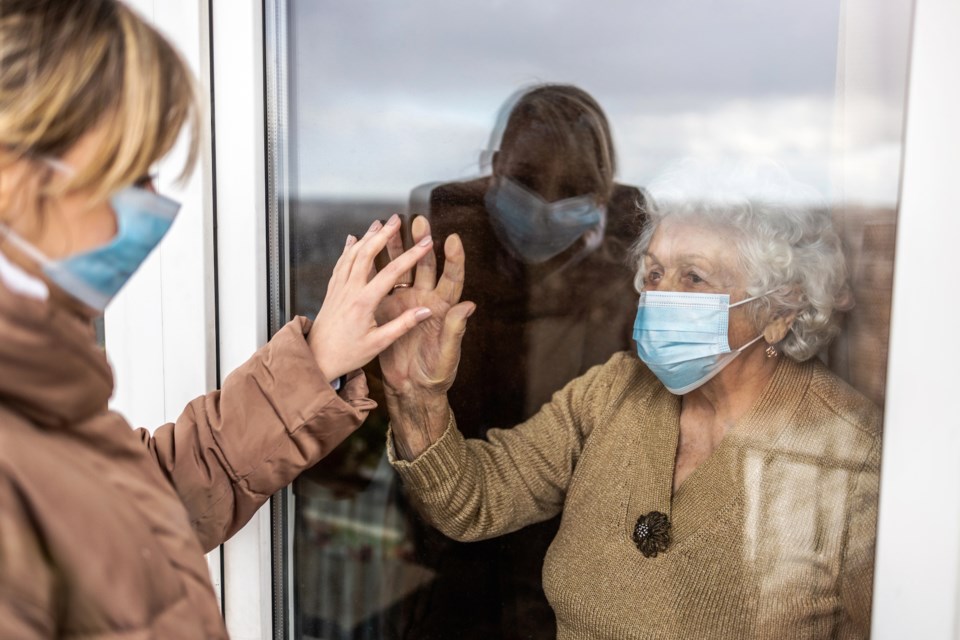

Failure doesn’t even begin to describe the horror that transpired across Ontario’s long-term care sector when the pandemic hit. In the first five months alone, residents of seniors’ homes accounted for more than 80 per cent of all COVID-related deaths in the province. Years from now, the early days of the virus will be remembered for the heartbreaking images of people standing outside nursing homes, trying to catch a glimpse of an elderly relative through a window.

All told, there were hundreds of COVID outbreaks at Ontario nursing homes.

“The province’s lack of pandemic preparedness and the poor state of the long-term care sector were apparent for many years to policymakers, advocates and anyone else who wished to see,” said the final report of the province’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission, chaired by Frank Marrocco, Ontario’s retired associate chief justice.

Private, for-profit LTC homes were hit especially hard. Numerous analyses have shown that residents in for-profit care died at a much higher rate than seniors living in non-profit or municipally run homes. At Roberta Place, a privately operated facility in Barrie, one particularly severe outbreak killed 71 people in just 41 days. At one point, all but one of the home’s 128 residents were infected with the virus.

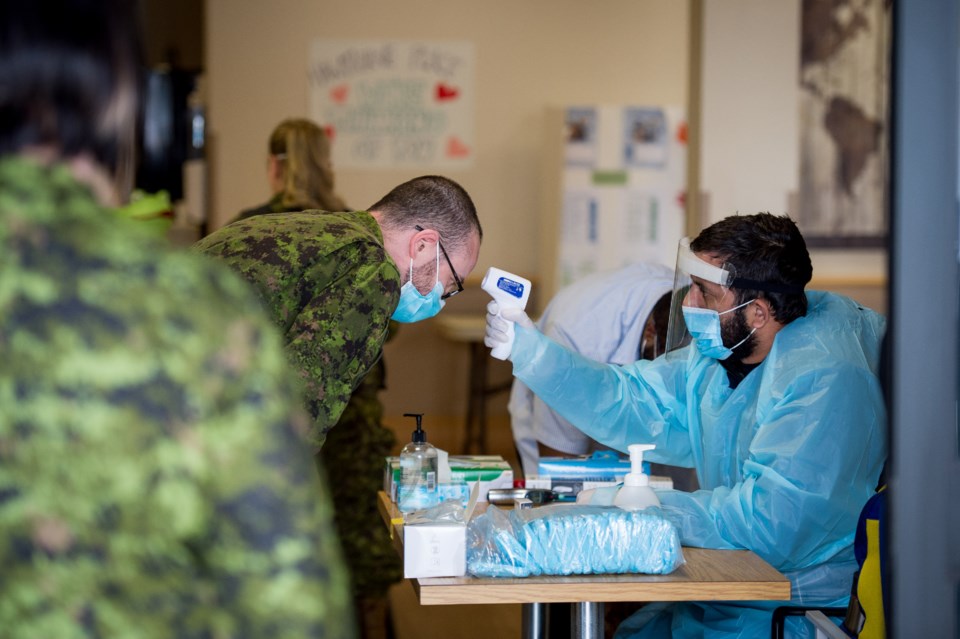

The situation was so dire that the Canadian military was called in to assist with outbreaks at seven LTC homes—all privately owned. What the military found was shocking: widespread neglect, malnutrition and filth. When soldiers arrived at one care home in Toronto, they discovered “feces and vomit on floors and on the walls,” and two residents with dried feces under their fingernails. According to documents filed with Marrocco’s commission, soldiers described the home as “a sh— pit.”

Policy experts and health care workers have been loudly calling for an overhaul of the system, with a particular focus on ending for-profit LTCs. During the recent provincial election campaign, the NDP, Liberals and Green Party all vowed to phase out for-profit nursing homes, accusing private operators of prioritizing revenue over residents. Progressive Conservative leader Doug Ford promised the opposite: to spend billions of dollars to add 30,000 new long-term care beds to the system while upgrading 28,000 others by 2028.

Ford won an even bigger majority on June 2, which means for-profit LTCs are not going anywhere. But the future of senior care in Ontario goes much deeper than a debate over private versus public nursing homes. Many seniors, revolted by what they saw on the news during COVID-19, don’t want to go anywhere near a long-term care facility. One poll conducted last year found that a whopping 96 per cent of Ontarians aged 55 and older plan to stay in their own homes or apartments for as long as possible.

It is those people who would benefit most from the worker co-op model.

“Co-ops are in some ways a middle ground that tend to be ignored by people who are debating whether something should be done by government or business,” says Budney, the University of Saskatchewan researcher. “We are medicalizing old age way too rapidly here in Canada, and there is always a push to institutionalize patients who could, with a different kind of assistance, do much better staying at home.”

After leaving her job in 2020, Turpin’s research led her to the website of the Canadian Worker Co-operative Federation (CWCF). It was a eureka moment. “I thought: ‘Huh, this actually might be what I’m thinking,’” she recalls. “I had an idea of a democratic workplace where PSWs have a real voice, I just didn’t have the word ‘co-op.’ So when I started talking to [the CWCF] about it, they said: ‘Yes, this has to happen.’ ”

Simply put, worker co-ops are owned by employees, which means everyone has an equal voice on how things operate, from wages to work hours. The cardinal rule of a co-op is: one person, one vote. Launched in June 2021, Home Care Workers’ Co-operative now has 17 caregivers who provide about 500 hours of service each week to clients in Peterborough and Durham Region. PSWs hired by the co-op can apply for membership after 480 hours of service, or approximately six months. “We have three PSWs who will be coming on board as members before the summer,” Turpin says.

Unlike other private companies that dispatch PSWs to people’s homes, the co-op concept is unique because it places a worker’s experience and expertise at the heart of the business model—which in turn, benefits the clients. Because everyone at the co-op is an owner, PSWs are able to spend as much time as they need getting to know their clientele and understanding their specific needs. They are also better paid than the average PSW, which means they are much more likely to stay at the company and foster even stronger bonds with the seniors they serve.

“Workers who know their clients and have relationships with their clients make better decisions for the clients,” Budney says. “The lower down the ladder the decision making happens, the happier everyone is going to be.”

Caroline Goodenough is definitely happier these days. At her home in Lakefield, Ont., she cares for her 71-year-old husband, George, a recent quadriplegic. “When he first came home from the rehabilitation centre, they wanted him to go into long-term care and my family and I put our foot down straight away,” says Goodenough, 60. “We said it’s not going to happen. I had heard so many horror stories of the long-term care facilities and how the patients are left in dirty, soiled diapers for hours on end, pushed in front of a window for hours on end.”

Goodenough’s husband originally qualified for seven hours per week of publicly funded homecare, but the actual service providers were all for-profit organizations. “They do not care in any way, shape or form about the patients,” Goodenough says. “I’m not saying the PSWs don’t care, but the actual pencil pushers, they do not care because they would chop and change the hours at will and they would send different people. It was just so frustrating.”

She recently switched to Home Care Workers’ Co-operative after qualifying for Family-Managed Home Care, a program that allows certain clients to choose their own publicly funded service providers. The difference has been monumental: 28 hours per week instead of seven, and two dedicated PSWs who feel like they “are part of our family.”

“Now that we have consistent care, George is not as anxious all the time,” she says. “He has continuity in his life. The two PSWs are both very caring individuals, and they listen to his needs. When he’s not having a good day, they can adjust their strategy, which means that George is more relaxed. He doesn’t feel that he is on a conveyor belt, you know? ‘Well, I’ve got 15 minutes to change your diaper, so let's get on with it.’ This is more about: ‘Let’s take care of you, George. How are you today?’ ”

Stories like that are what keep Turpin striving for more. Convinced that her co-op idea can play a major role in the future of elder care, she is now working with Dr. Simon Berge, director of the Research Centre on Co-operative Enterprises at the University of Winnipeg, to develop a proposal for a “federated care co-op”—essentially “a co-op of co-ops,” says Berge. It would act as an umbrella organization to support a network of PSW co-ops across the country, providing business services such as invoicing and marketing (and possibly even a pension plan) so workers can focus their energy on providing quality care.

Berge and Turpin requested federal and provincial funding to implement their proposal in February. “To date, no government has responded to our request,” Berge says. Undeterred, they’re in the midst of working on a scaled-down proposal: a single “care co-op incubator” that would provide basic back-office support to rural Ontario communities. Berge is optimistic, noting that other PSWs have reached out in recent months for advice on how to develop their own in-home caregiver co-ops.

Could the co-op model be rolled out in long-term care homes? If PSWs had owned and operated some of those facilities during the onslaught of COVID, would fewer residents have died?

One thing is certain: without government engagement, the capital required to build or acquire a physical building is likely out of reach for a small team of caregivers. But that doesn’t mean it is completely out of the question. Parts of Europe have already proven what is possible.

Gulliver Cooperativa Sociale, founded in Moderna, Italy, in 1996, manages a care home called Cialdini, which remained COVID-free well into the first six months of the pandemic. The co-op attributes its success to quick lockdowns, pandemic-specific worker training (it employed three full-time specialists to coach staff), its small size (fewer than 100 beds) and a united workforce.

Mariaje Jesús Zabaleta is general manager at Gestión Servicios Residenciales (GSR), a worker co-op in Spain’s Basque Country that oversees 26 long-term care homes. In March 2020, she was tasked with finding protective masks. As Canada scrambled to source masks out of China, working miracles in procurement and even accepting PPE that had expired, Zabaleta called a former colleague at Mondragon Assembly, an equipment manufacturer in Kunshan, an hour west of Shanghai.

“He was my friend from work,” says Zabaleta, in an interview with Village Media. “So I asked him for help.” With one call, she secured 2,000 masks in a few days, and a new machine to make more within a month.

As COVID goes, it may seem strange to hold up a group of co-op care homes in Spain—where case counts are still among the highest in the world—as a symbol of success during the first wave. But at GSR’s homes, which are scattered throughout the intensely green hills just south of Spain’s border with France, Zabaleta tracked fewer deaths from COVID than she did from the flu in previous years.

And while Ontario was putting emergency orders in place to restrict underpaid PSWs from moving between care homes, GSR saw its workers dig into the crisis in the same manner they always do: as a team, empowered and loyal.

After two years of working with GSR, staff members become worker-owners—and whether they are a physiotherapist or a cook, their voice is heard. If an employee sees something that needs changing, they submit a proposal. And every year, the staff collectively determines the company’s objectives.

There are other perks. At GSR, staff-to-resident ratios are higher, so burnout is rarely an issue. Workers collaboratively set their own schedules, so they’re able to meet obligations outside of work. And once a year—because they decided it would be so—workers get a share of GSR’s profits. No surprise, staff turnover is low.

“We've known for quite a while that there is a problem with long-term care facilities, but the public awareness on it was not exactly there. COVID changed that,” says Catherine Bigonnesse, an assistant professor at the University of New Brunswick, and a gerontologist who studies healthy aging and aging-in-place. “So it’s time now to shift. Attention is on the issue now. There is a need for change in how we care for our seniors.”

Although Bigonnesse is the first to admit there “is no magic bullet” or “a one-size-fits-all solution,” she sees the potential benefits of PSW-owned co-ops. “This is one among multiple solutions we’ll be able to put in place,” she says. “I’m a fan of aging in place, providing options for seniors to avoid going into long-term care, but let’s not forget that it is still required. At some point, people will need long-term care facilities. But we need to provide other options to delay the time where they have to go into an LTC.”

Turpin wants to be that option—and she is optimistic others will follow her lead. “The answers are so clear,” she says. “It's just so frustrating because you see the answer. Study after study shows that seniors want to age in place, which is so much less expensive than a hospital bed or a long-term care bed. We should be doing what people want, and saving taxpayers money.”

If her idea saves some lives, even better.

A veteran journalist, Jen Cutts was a long-time copy editor and contributor at Maclean's magazine. Her writing has also appeared in Today's Parent.